- By Karina Bontes Forward

In 1992, United Nations Conference on Environment and Development took place in Rio de Janeiro - hence the name of the current Rio+20 Conference, being its twentieth anniversary. There, the cariocas (common name for Rio’s inhabitants), marched the streets in protest, chanting "what is the use of all this ecology if our people are oppressed and massacred!".

In 1992, United Nations Conference on Environment and Development took place in Rio de Janeiro - hence the name of the current Rio+20 Conference, being its twentieth anniversary. There, the cariocas (common name for Rio’s inhabitants), marched the streets in protest, chanting "what is the use of all this ecology if our people are oppressed and massacred!".

Last Wednesday’s protest in downtown Rio was also full of cries, chants and banners, as not only the cariocas but thousands from the world’s different countries converged on the main street under a grey spitting sky. But the chants were different, and the banners had different writing, this time with things like: ‘Por um mundo verde y justo’ (For a fair and green world), ‘As mulheres dizen nao ao capitalisme verde’ (Women say no to green capitalism), ‘Desmantelemos el poder corporativo’ (Dismantle corporate power).

Massive earth-painted balls balanced on hundreds of fingertips, flags from all over the world were waving (predominantly Latin American), men and women orated passionately and strongly to the marching masses about social and environmental justice from the tops of floats, and percussion troops and free whistles ensured the grounding vibes and beautifully invigorating noise pollution that accompany large-scale protests.

Massive earth-painted balls balanced on hundreds of fingertips, flags from all over the world were waving (predominantly Latin American), men and women orated passionately and strongly to the marching masses about social and environmental justice from the tops of floats, and percussion troops and free whistles ensured the grounding vibes and beautifully invigorating noise pollution that accompany large-scale protests.

And the message was different. Instead of demanding poverty eradication over ecological action, painting it as separate to social injustice, the chants championed ecological integrity as well as equal rights and respect for all humans and poverty eradication, which is demonstrative of how different the dominant paradigm is now - people everywhere are realising that the two are not so separate.

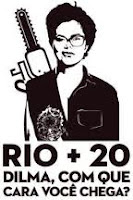

Brazil’s government, headed by President Dilma Roussef, recently relaxed the laws dealing with deforestation in the Amazon, creating a massive backlash in not only environmental groups, but in Brazilian civil society and the wider global community. The laws on deforestation had been tightened previously, limiting the previously rampant destruction that had been happening and securing protection for large tracts of forests - but now the country is backtracking.

‘Dilma, com que cara você chega?’ (Dilma, how can you show your face?) is the line branded underneath a caricature of the president wielding a chainsaw. Stuck all over the walls in Rio, on protest banners and on postcards around the place (especially at the People’s Summit), it is clear that a good part of Brazilian society is not happy with the move, least of all the indigenous peoples, who can see that once again their right to sustainable use of their lands, and indeed their access to resources, is to be threatened. The decision to introduce this legislation in the weeks before the world’s largest environmental summit, what UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has called ‘a once-in-a-generation opportunity’, is a bad move for a host country.

‘Dilma, com que cara você chega?’ (Dilma, how can you show your face?) is the line branded underneath a caricature of the president wielding a chainsaw. Stuck all over the walls in Rio, on protest banners and on postcards around the place (especially at the People’s Summit), it is clear that a good part of Brazilian society is not happy with the move, least of all the indigenous peoples, who can see that once again their right to sustainable use of their lands, and indeed their access to resources, is to be threatened. The decision to introduce this legislation in the weeks before the world’s largest environmental summit, what UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has called ‘a once-in-a-generation opportunity’, is a bad move for a host country.

This is obviously a relevant problem in the context of Brazil and Rio+20, but it’s also hugely important for the world. It was one of the central themes focussed on at the protest, and it is so very reflective of the practice of too many states - the actions don’t reflect the words. The world has globalised considerably since 1992, and the need for participatory decision-making is more important than ever, but the voice of civilian actors in the final process has been little heard. The final outcome document of the conference states in the first paragraph that conclusions were reached, together with the heads of state and governments, ‘with full participation of civil society,’. Such is the absurdity of this statement that its removal was requested by some of the major groups representing civilians. The input of civil society in the final document was largely excluded, paragraphs on inclusive participation were struck out, the creation of a UN High Commissioner for Future Generations was brushed aside; business-as-normal is back on the bandwagon as far as most governments and big business are concerned.

Although the outcome text, labeled ‘The Future We Want’, would probably be more accurate if it was called ‘The Future They Want’, it is not to say that the conference was a failure. The attendance of 50,000+ people to discuss the future we want included many civilians, and the ideas sharing, collaboration and inspiration that can be drawn from such global meetings is a success in itself. I personally met many people who were attending the official conference and who were discouraged by the lack of progress that comes with trying to get 190 nations agreeing on a consensus text, but who had nonetheless come away with new friends, networks, agreements, ideas and with some sense of assurance that there are others who give a damn and are doing something about it.

As I myself did. My personal yo-yo, of going to talks and workshops where a sense of apathy and unresponsiveness, and not to mention the lack of urgency, were the overriding feelings, and then going to inspirational panels of speakers where you feel it is absolutely impossible to not have hope, to not believe in the creativity, innovation and willpower of the human species in the face of destruction, sent me on a bit of an emotional rollercoaster. Marching with those 60,000 people reminded me that there are many out there who are concerned, really concerned, about the lack of action. Who are demanding a better world, now and in the future, for them and their children.

As Kermit says, it’s not always easy being green, especially when the mainstream is not, but realising there is a worldwide movement of people screaming for change in all different shapes and forms makes you feel a little less lonely. It’s too late to not have hope, and although us humans can be destructive and dangerous, we can also be compassionate and benevolent, and I choose to believe in that, together with those multicoloured people carrying green banners.

No comments:

Post a Comment